Outer space is getting busy. The United States and the former Soviet Union used to be the key players in exploring the infinite skies above Earth. Now, nation after nation is getting in on the action. And with mining, tourism, exploration, communications and warfare all on track to leave Earth’s atmosphere, space law has become one of the most topical, groundbreaking areas for legal scholars.

Valerie Oosterveld is a Western law professor with a background in international criminal justice. She is also a faculty member in the university’s Institute for Earth and Space Exploration, where she specializes in outer space law. She finds herself in a fascinating and consequential field of research.

The International Criminal Court and the International Space Station are very far apart, literally and figuratively. How did you come to have legal expertise relevant to both?

In law school, I already knew I wanted to work in the field of international law. After graduate school, I had the opportunity to become a lawyer at Global Affairs Canada, working on the creation of the International Criminal Court. In 2005, I became a faculty member at the law school here at Western. In that role, I taught a course called Public International Law, which covers outer space law, the law of the sea and the law of land, among other topics.

Each year since, I’ve taught a module on outer space law as part of this course. Every single time I taught it I thought, “This is fascinating.” When Western created the Institute for Earth and Space Exploration, the director asked who from the Faculty of Law would like to be a part of it. I put up my hand.

That choice allowed me to collaborate with people at the Institute and teach a course entirely dedicated to outer space law. It has been a lot of fun. My students and I not only study the nuts and bolts of outer space law, but we do things like speak to Canadian astronauts and screen the students’ favourite space movies to discuss the legal issues they raise.

What’s a science fiction premise that raises interesting legal issues?

I get asked quite a bit about what would happen if aliens came to Earth. On Earth, there are clear rules about when countries can use force against other countries, which is only legal in certain circumstances, such as self-defense. How does that apply when the adversary is not another state but aliens? It’s very likely self-defense would apply to Earthlings fighting back against aliens who are destroying the planet. Then we get into really interesting questions like what happens to captured aliens? What rights would they have?

Space law bridges science and science fiction. How much of what you’re dealing with has to do with outer space as we interact with it now, and how much with speculative scenarios?

Space technology is advancing rapidly, often outpacing legal frameworks. The dynamic between evolving science and law, in areas like space mining, tourism and satellites, is fascinating.

The rapid development of space resource extraction from the Moon, Mars or asteroids is sparking ongoing discussions in the space mining industry. There is a United Nations committee discussing the existing legal framework, which needs to be developed in more detail to address questions like, should space mining happen? If so, how much? Where? By whom? What is the liability? What kind of coordination needs to happen?

Spacefaring nations and soon-to-be-spacefaring nations that want to benefit from space resource extraction need certainty on those questions in the near future.

With respect to satellite law, there are quite a few questions about the environmental impact of SpaceX, OneWeb and others launching thousands of mega-constellation satellites, which re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere after five years and burn. Some say we’re in a massive scientific experiment with the Earth’s atmosphere, and we don’t know what the outcome will be.

Satellite law has fallen to a specialized international organization called the International Telecommunication Union. It has been successful in regulating and standardizing who is authorized to launch satellites and where satellites are placed in orbit so they don’t crash into each other. However, there’s a disconnect between that and the consideration of the environmental and health impacts of permitting so many satellites.

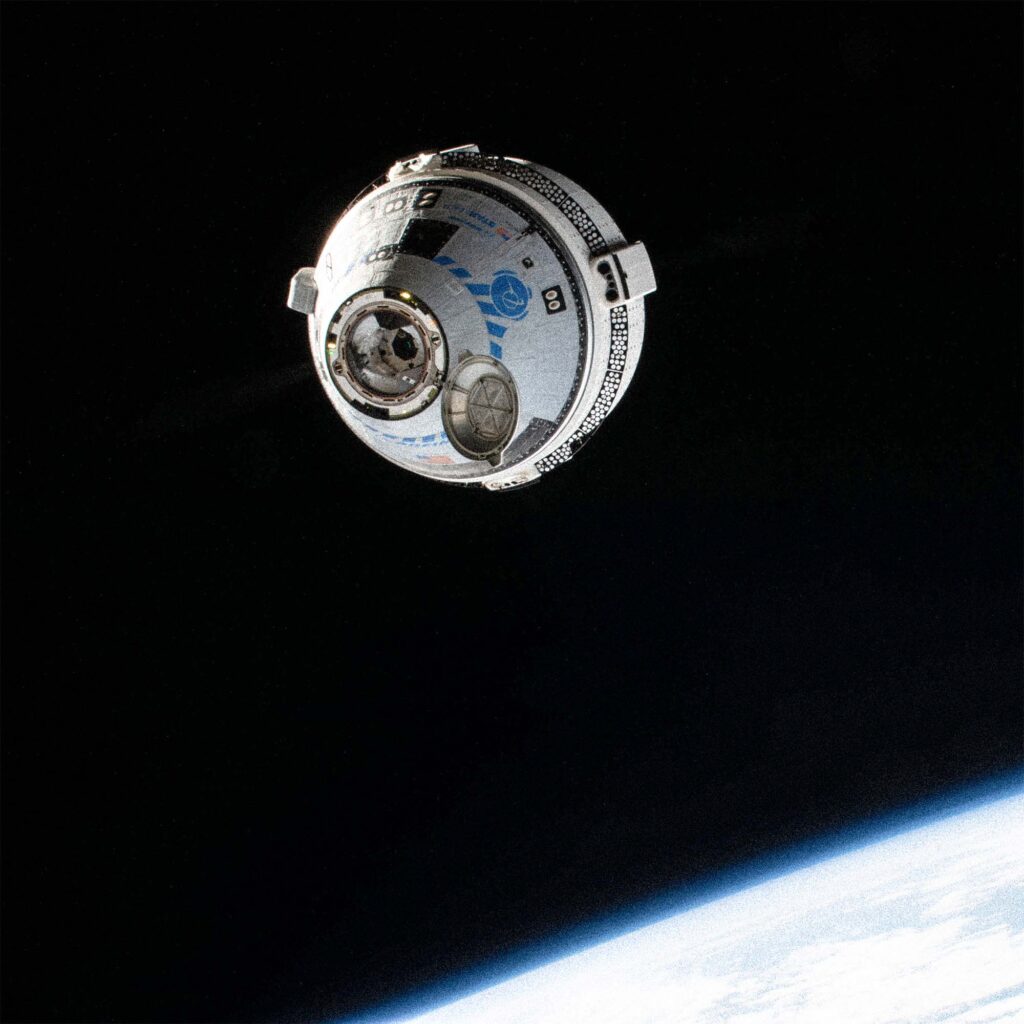

In 2023, Virgin Galactic took the first ticketed tourists to the edge of space. There’s currently no clear coordination between existing airspace law on Earth and laws governing outer space. If you have many space tourist launches, what kind of coordination do we need between these two areas of law?

To an outsider, this world of mining and space tourism has a “wild west” vibe. How much do the old frontier and this new frontier have in common?

I don’t think it’s the wild west. We have the Outer Space Treaty, which provides a framework for everything that takes place in space. It says activities in space must be authorized and continually supervised by the country responsible. It sets out liability. It says countries using outer space must do so in accordance with international law, which includes laws on the use of force and waging war. We need more detailed guidance, but that doesn’t mean “anything goes.”

How ready are we for what’s coming?

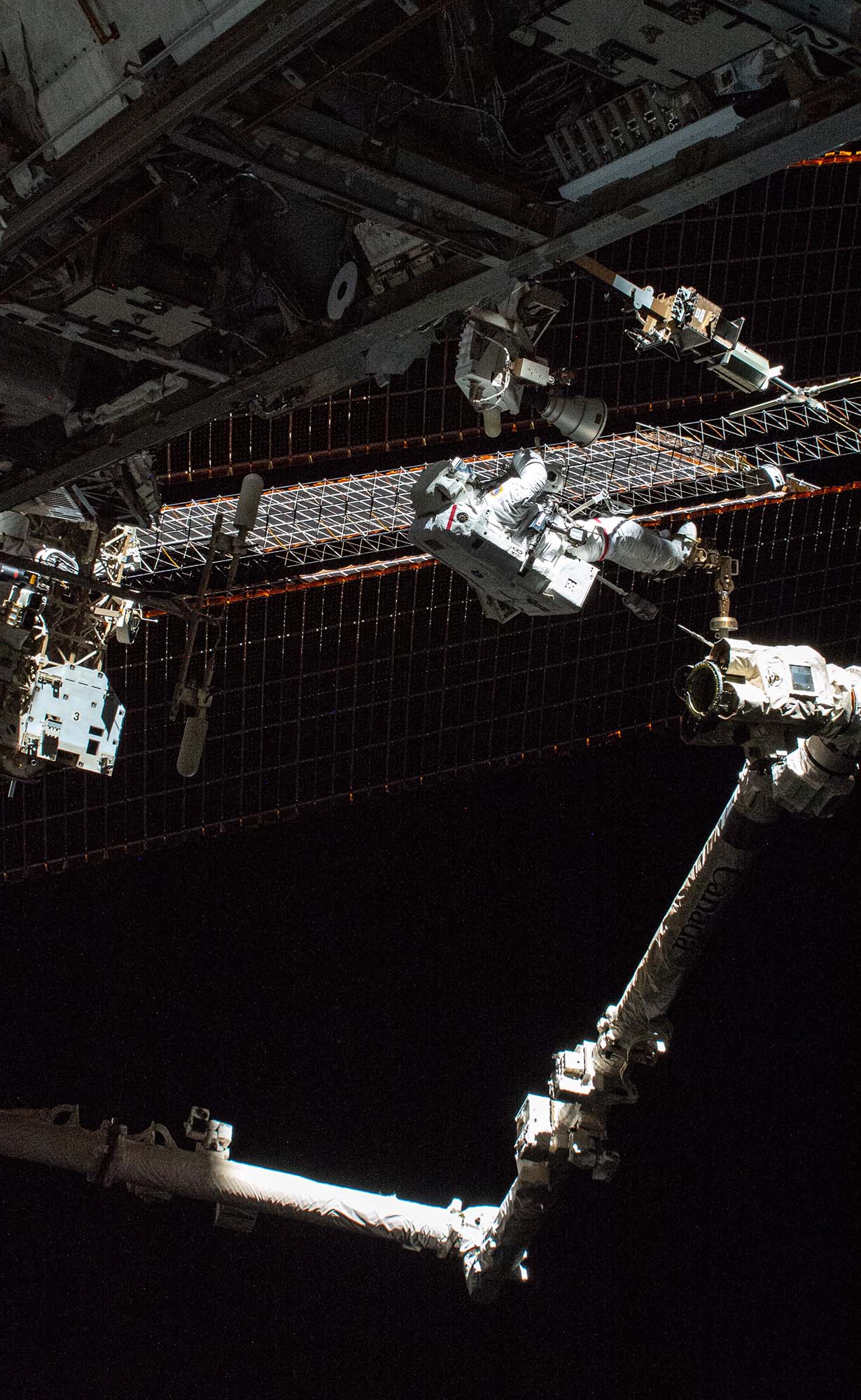

The challenge is in ensuring we have the details that guide nations and private entities in their activities in space. Let’s take the example of how criminal law might be applied to space settlements. The International Space Station (ISS) offers some precedent. It’s governed by an intergovernmental agreement and each partner country retains jurisdiction over their citizens. They can prosecute their own astronauts who commit a crime on board the ISS. That country can also defer prosecution to the country of the victim, or the country of the module in which the crime took place. Say a Japanese astronaut commits a violent act against a Russian cosmonaut in an American flight module. Japan would have primary jurisdiction to prosecute the crime, but it could cede that jurisdiction to Russia or the United States.

None of this has ever been undertaken in practice because there hasn’t been a crime committed on the ISS. But the very fact we have this framework means we could apply it to Mars or the Moon, if there are human settlements there.

Would that framework also cover, say, an international race to extract resources from asteroids?

Yes. Everyone agrees that wherever humans are operating, human law must follow them to guide and constrain their behaviour. What if we’re sending robots to do space mining? What laws apply then? The answer is the same laws, as humans are responsible for those robots.

The Outer Space Treaty says two important things about the exploration and exploitation of outer space. First, it shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries, which means the benefits of space exploration must extend even to states without the capacity for a space program.

The current treaty doesn’t say how that sharing should take place. Spacefaring nations are not leaning in the direction of financial sharing, but scientific sharing or something else instead.

Second, the treaty says there can be no territorial claims in space. No state can acquire property rights to celestial bodies. That has raised the question, “How can people use space resources without claiming property rights?” They’re discussing exactly this in the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. Every state agrees you can use space resources for scientific study. A number of nations have already brought back space rocks, and no other nations have objected.

How would that work on an industrial scale?

We haven’t answered the question for much larger extractions. Is there a size limit? What if the extraction is for commercial profit instead of scientific study? What are the rights to the resources extracted? The U.S. has a very clear position that as soon as minerals or other resources are removed from their original site, property rights apply. That position is being debated.

Some non-spacefaring countries are worried if we don’t adopt detailed law soon, they will come too late to reap any benefits. That’s a fair concern.

How hard is it to adapt existing Earth laws to space?

I’ll give an example. For some time, we’ve known humans need to avoid creating more and more space debris, particularly in low-Earth orbit. It’s very dangerous, as it can hit spacecraft and satellites with impact speeds up to 15 kilometres per second. As debris levels rise, collisions could create even more debris, potentially making future launches from Earth extremely hazardous. How does environmental law developed for use on Earth apply to the debris field? The precautionary principle is already being applied, as spacefaring countries work to reduce the creation of new space debris to try to avoid creating future problems. But it’s not clear yet how other environmental principles originally created for Earth, like sustainable development, apply in space.

You have a high-profile background in human rights and applying feminist principles to the law. Is it a motivating force for you to ensure those values are reflected in space law?

Absolutely. Feminist analysis of international law requires me to think about what’s missing. What points of view have been overlooked? I apply a feminist analysis when considering the prosecution of those who commit genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity. In international criminal law, that means ensuring victims are heard, including victims of sexual and gender-based violence, who have been overlooked for decades and centuries.

In space law, I still ask whose voices are not being heard. We have, for example, questions of Indigenous rights. Are Indigenous Peoples being consulted on the disappearance of dark and quiet skies due to bright satellite constellations? Are they being consulted on how their beliefs about the sanctity of the Moon are being impacted by plans to mine the Moon?

In the time you’ve been working in space law, how has it changed and what do you see coming next?

When I first started teaching space law, a key issue was space debris. It’s still a concern today, given the growing number of satellites and large debris fields created by anti-satellite weapons tests by China, Russia and others. In recent years, though, it has become more urgent to ensure international space law provides adequate guidance to address the mega-constellations of satellites, space tourism flights and plans by countries and private companies to mine space resources on the Moon, Mars and asteroids. The field is evolving rapidly—it’s great for keeping my mind flexible.

What is it like to work in such a groundbreaking field of study?

I love it. I’ve had the chance to work with people like Dr. Adam Sirek, a physician and Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry professor who specializes in aerospace medicine. We have discussions about how to treat medical conditions in space, and how the law applies to that. I have other conversations about space security. I have super interesting interdisciplinary discussions with colleagues from science, philosophy, medicine and business—you name it.