We throw out too much food, but there are ways to cut the waste and put it to good use.

Every day, in kitchens across Canada, a half-eaten meal or a bag of salad greens slips to the back of the fridge. It hasn’t gone off yet, but give it a day or two and it will. And when it does, it will end up where so much of our food does: the composter, green bin or, more often than we want to admit, the trash. We may feel a brief pang of guilt as we scrape the dinner plates or tie off the bag, but then we remind ourselves it’s nothing compared to the waste produced by restaurants, grocery stores and supply chains.

We’re wrong.

Multiplied across the country and around the world, households throw out the equivalent of a billion meals a day, even as hundreds of millions of people go to bed hungry and one in three experience food insecurity.

North Americans are some of the worst offenders. In Canada, up to half the food produced for consumption never gets eaten. That’s enough to feed every Canadian for five months, or every person in Denmark, Finland and Sweden for an entire year. This waste is not just an ethical failure. It is an economic and environmental failure too. Every time food is wasted, everything that went into producing it is also wasted.

That leftover lasagna you slid into the bin after a long week carries with it the embedded carbon, water, land, labour and transportation that brought it to the grocery store and then your kitchen. If it goes in the green bin, it’s turned into compost or renewable energy. But if it’s thrown in the garbage, it ends up in a landfill, where it can contaminate groundwater and release methane, most of which won’t be captured for energy and will instead be released into the atmosphere.

So, what can we do? This is where Western researchers Latifeh Ahmadi, Paul van der Werf and Naomi Klinghoffer come in, each approaching the problem from a different angle, but with a shared sense of urgency that food waste is both preventable and solvable.

Ahmadi, professor in Western’s Brescia School of Food and Nutritional Sciences, sees the home as the front line in the fight against food waste. In Canada and other developed countries, the largest portion of food waste, she says, doesn’t happen on farms or in transport, but in our kitchens. “Half of the food we waste happens in a household,” says Ahmadi. “Instead of pouring more energy, land, fertilizer and water into producing food, we need to focus on preventing waste.”

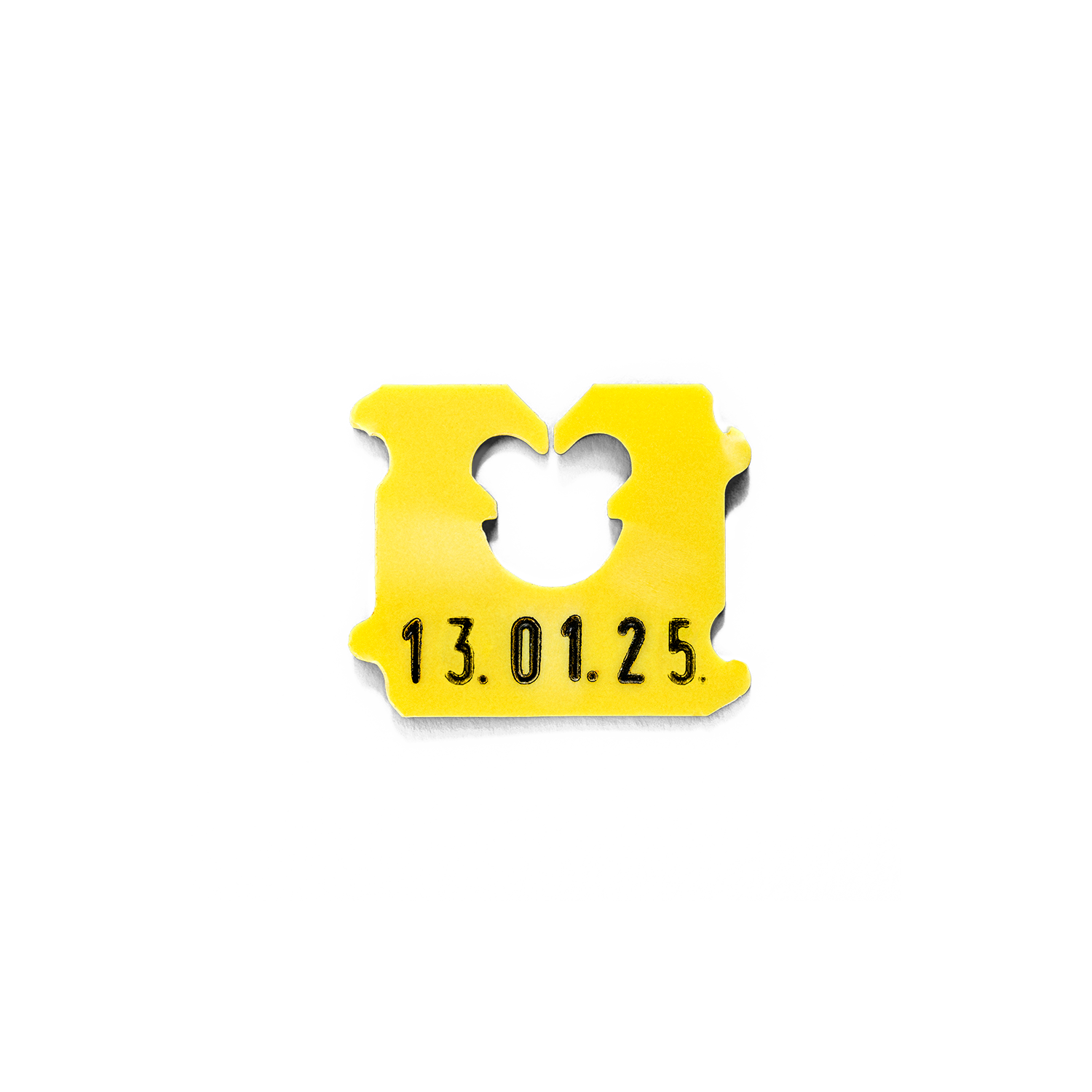

Worst of all, much of what we throw away is perfectly edible. Ahmadi’s goal is to reduce—or, preferably, prevent—household food waste through education and better information. Her advice is simple: plan meals, check what’s in your fridge before shopping and know that “best before” isn’t “bad after.” For foods where there’s a safety risk, use expiration dates. Milk can spoil and become unsafe. Yogurt is different—it might taste a little sour, but it isn’t harmful even after the date.

She also stresses the value of freezers. Freezing leftovers right away keeps them safe for up to two months, while choosing frozen vegetables prevents spoilage, saves time and money and offers the same nutritional value as fresh produce.

But food waste isn’t confined to homes. In a study with her graduate students, Ahmadi found it is also widespread in food services. Their research in a campus restaurant showed dinner generated the most waste, consisting mainly of carbs, while plant proteins were rarely discarded. Waste was especially high among those on prepaid meal plans compared with pay-as-you-go diners. Ahmadi argues the solutions are clear: serve smaller, balanced portions, reduce carb-heavy defaults, improve taste and give students options for saving leftovers.

Ahmadi also sees potential in technology: “AI could automatically measure food waste by comparing images of plates before and after meals. Early tests using phone photos show high accuracy with little effort. With the right tools, this data can drive meaningful change.”

Data is at the centre of Paul van der Werf’s work. An adjunct professor in the department of geography and environment and in the Ivey Business School, van der Werf approaches food waste like a detective. He audits waste streams, surveys households and uses the data to build a clearer picture of what we’re up against.

In a study of more than 1,200 households in London, Ont., van der Werf found each threw away an average of six edible portions a week—roughly $600 per household every year. Households with children wasted even more. And while many assume food waste is a problem of affluence, income isn’t the main driver. Lower-income households often waste as much food as wealthier ones, just in different ways.

Access to this kind of information helps municipalities make more informed decisions, from adjusting green bin sizes to developing education campaigns that resonate with residents. Grounding these policies in real-world evidence also allows local governments to establish a baseline for testing and refining strategies and tracking progress—or lack thereof—over time.

Like Ahmadi, van der Werf sees lifestyle shifts as the key to driving behaviour change, which he believes lies in grasping the underlying motivations. Money appeared to be the primary motivator for London, Ont. households, van der Werf and his team found.

“If you tell someone they’re wasting $20 a week, it’s like watching them crumple up a $20 bill and toss it,” says van der Werf. “In my research, I was able to use dollars wasted or saved as a motivator and saw a 30 per cent reduction in food waste thrown out at the curb, measured through garbage samples collected before and after the intervention.” What’s more, this reduction was still evident when samples were taken from these households a few years later.

In a recent report, Good to the Last Bite, van der Werf and his team employed a data-driven model to analyze food-wasting behaviour and provide household consumers with practical advice to help them reduce food waste, which translates to more money in their wallets, while at the same time helping the environment. The report offers five simple steps to stop waste: plan meals ahead of time, make a grocery list and stick to it, store food properly, prepare the right amount of food and use leftovers.

In nature, there’s no such thing as waste. Everything is reused.

Whereas Ahmadi and van der Werf focus mainly on waste prevention, chemical and biochemical engineering professor Naomi Klinghoffer focuses on reinvention.

We generate significant waste through daily activities while consuming large amounts of energy and materials. Landfills take up valuable land, emit greenhouse gases and contribute to plastic pollution in oceans and waterways.

At the same time, resource extraction is accelerating to meet material demand. Mechanical recycling can handle only certain materials, but chemical recycling breaks down all types of waste, including food waste, into chemical building blocks that can be reused to create materials or low-carbon fuels. This approach supports a circular economy that benefits both society and the environment.

“In nature, there’s no such thing as waste,” Klinghoffer says. “Everything is reused. We need to shift to a mindset where all by-products are used productively.” At Western’s Institute for Chemicals and Fuels from Alternative Resources, Klinghoffer and her team work with biochar, a carbon-rich substance created by heating organic waste in an oxygen-free environment, a process called pyrolysis.

Biochar looks like charcoal, but it’s far more versatile. Adjust the temperature or heating rate, and you can “tune” it for different uses—enhancing soil health, filtering pollutants from water, reducing the carbon footprint of cement, even creating conductive materials for electronics. Unlike many processes that release carbon back into the atmosphere, biochar locks it in place for centuries.

Looking ahead, Klinghoffer envisions this innovative, environmentally friendly process may have applications beyond industry. Small-scale pyrolysis units could one day allow communities, or larger farms, to process food waste locally, converting scraps into soil amendments, energy or other valuable resources.

Reducing food waste alone won’t end hunger. Nor will turning the waste we’re producing into alternative products like compost or biochar.

Food insecurity is tied to larger systemic barriers, but every meal we can save is a step in the right direction. Some of the answers are old-fashioned: planning meals, portioning properly and preserving food before it spoils. Some, like biochar, are cutting-edge. Paired with technological innovation and smarter policies, these interventions and simple steps have the potential to transform how we prevent, reduce and repurpose food waste. “The challenge is vast,” Ahmadi says, “but so is the potential. By blending traditional knowledge with modern innovation, and pairing individual action with community-scale solutions, we can move toward a future where less is wasted and what waste we have is put to productive use.”